In these articles on the human history of Puangiangi, I’m going to concentrate on things directly related to the island. What plays out on Puangiangi is just a sidebar in the tumultuous events of the time, but there are plenty of good reads on the bigger picture available, some of which I refer to in this article.

This portion of the history of Puangiangi starts with some fragments about earliest settlement and goes through to the island’s alienation from Ngati Koata collective ownership. As I’m not a trained historian, and as I’m working from old papers which will never tell the whole story, I would be very keen to get more material from readers, especially descendants of those who appear in this article, and to add or correct information as required.

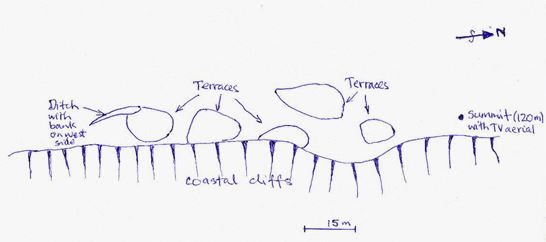

Consultant ecologist Geoff Walls made a brief archaeological survey of Puangiangi in 2012. He, Chris Horne and the late Barbara Mitcalfe also identified the plants karaka, ti kouka and rengarenga, all well established on the island today, as highly likely to have been brought by early settlers or visitors, as they were in many other places. Geoff identified several sites of occupation, including a pa site on one of the high points, which would have given a terrific view. People were relatively close by at Wairau from almost the earliest times of settlement in Aotearoa, and the pa might date from near to then, or right up to the Kurahaupo peoples of the 17th Century, or beyond.

Quite a few stone adzes have obviously been picked up on the island over the years. On arrival in 2012 we found some on a shelf in the house, and even one incorporated into the fireplace. The stone would have been quarried from nearby on Rangitoto Ki Te Tonga/D’Urville (I’ll largely use “D’Urville” to distinguish the main island from the modern-day Rangitoto group, which includes Puangiangi). At Woolshed Bay an exposed soil profile contains charcoal and burnt stones. Argillite flakes are in that midden and on the beaches, indicating that material was brought from D’Urville and worked there. Small rounded stones possibly suggest that the site at Woolshed Bay was gardened.

It’s possible that when Puangiangi was fully forested, it held water for most or all of the year, and so might have been settled. It may instead have been the focus of seasonal foraging trips. We just don’t know. We are not aware of any caves, and certainly no burial sites are known. Ross Webber told me once that he had been asked not to build at a particular site, but the significance of this is not known.

The Kurahaupo alliance mentioned above is shorthand for Ngati Apa, Rangitane and Ngati Kuia, and also incorporates the “original peoples” found when the three iwi first arrived in the 17th Century or earlier. The 1600s to the early 1800s were a period of relative stability in the region. Ngati Kuia had a main settlement at Ohana, at the southern end of D’Urville, while Rangitane were at Bottle Point on the western side. (For a comprehensive account of the waves of settlement and conquest which came to the northern South Island, refer to Te Tau Ihu o te Waka, Volume 1, by Hilary and John Mitchell, Huia Press, 2004.)

Up north at Kawhia from the late 1700s, some Tainui iwi were finding the going tough, with sufficient conflict that in about 1821 Te Rauparaha had to lead a heke of some 1500 Ngati Toa, Ngati Koata and associated hapu away from Kawhia, south to Taranaki. Te Rauparaha went further south the following year, conquering Kurahaupo lands right down to Te Whanganui-a-Tara, and settling on Kapiti. The Kurahaupo remnants made plans with relatives living in the Sounds and on D’Urville to extract utu.

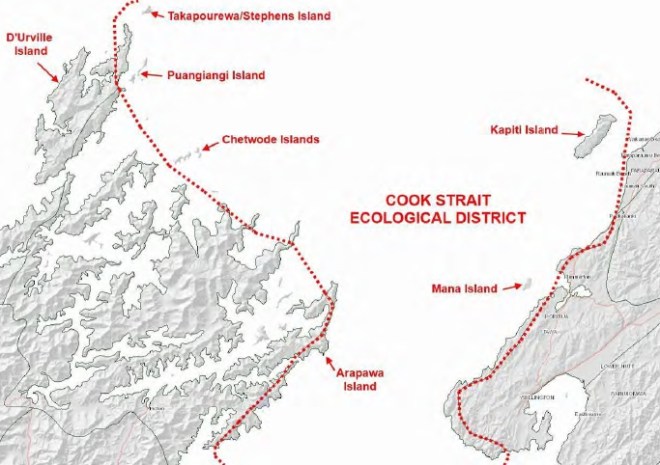

In 1824-5, the warrior chiefs Waihaere, Kerengu and Tutepourangi (Ngati Kuia) led a party of 2000 in the battle of Waiorua at the northern end of Kapiti, but they were beaten. Tutepourangi was captured by Te Putu, one of the principal Ngati Koata rangatira. Tutepourangi threw his patu into the sea, but Te Putu made him dive down and get it. It was then discovered that Te Putu’s young brother-in-law Tawhe had been taken by the retreating remnants. Two waka set off in pursuit, and Tawhe was eventually found safe and well at D’Urville by the party in the waka Kapakapapanui. On Kapakapapanui were Ngati Koata rangatira Mauriri II, Te Putu, Te Patete and the captive Tutepourangi. In return for his life and that his iwi might live in peace among Ngati Koata, Tutepourangi stood up in the waka and ceded Ngati Kuia’s lands to Ngati Koata. The lands included D’Urville and the Rangitoto Group (special thanks to George Elkington for relating this to me). In subsequent years marriages were arranged to cement the bonds of Ngati Kuia and Ngati Koata. Tutepourangi became greatly respected by both iwi, but met his end during later raids by Te Rauparaha.

On Rangitoto Ki Te Tonga, Ngati Koata settled at Te Marua (where Turi Te Patete, son of Te Putu, signed the Treaty of Waitangi), Moawhitu, Manuhakapakapa, Ohana, Haukawakawa, and also on Tinui. European settlers were present from the 1830s and Port Hardy became a place for ships to regroup before discharging settlers, including my ancestors, into Wellington.

The New Zealand Company acquired the entire northern South Island in 1839. The fledgling government subsequently reduced the amount of land involved in this highly questionable purchase, but settler pressure for land led to official government purchases in the 1840s and 1850s. D’Urville and environs were excluded from these sales.

The creation of the Native Land Court led to a mechanism whereby traditional ownership might be force-fitted to the new template of land titles. This process came to D’Urville in 1883, when 79 Ngati Koata owners were identified and given undivided title to the island and its surrounds. Ngati Koata pre-eminence was recognised by the Court, by virtue of Tutepourangi’s gift.

It took a further 12 years for D’Urville to be partitioned further, but in 1895 it was divided into 11 blocks. Each block had a list of owners- a subset of the 79- in undivided shares. Each owner of 80 acres on the main island also got one acre of the surrounding 55 islands (including Puangiangi), islets and stacks, again undivided.

The owners were prevented from selling a block or their individual interest in it. They could only lease it on a 21-year term. The idea was that this would prevent the owners from being dispossessed of their lands, but in reality it served more to stymie them from getting on with life. They had already seen in the last decade their potato crops fail due to blight and drought, their sheep killed because of an 1885 outbreak of scab, forestry and mining ventures fall over, and many had been part of the general exodus from the region around 1890. Rents were not enough to develop land wherever the owners might have been living by then, and indeed were often not enough to live on. Those who stayed on their land were often not generating enough income to improve their farms, and there was precious little labour around given the general depopulation.

Amongst those who had stayed in the rohe, Hoera Te Ruruku is listed in the annual Sheep Returns to the House of Representatives as running a flock of 45 on Puangiangi in 1886 and 42 in 1887. Te Ahu Pakeke (Joe Hippolite) had a similar flock on Tinui. Anthony Patete’s 1997 report to the Waitangi Tribunal has Hoera Te Ruruku taking over Tinui in 1889 from the Hippolites, then farming at French Pass, and then back on Tinui in 1911. Descendants of Hoera Te Ruruku identify him more with Tinui than Puangiangi, and indeed his parents lived on Tinui. Hoera Te Ruruku was a prominent rangatira within Ngati Koata and brought the LDS religion to the region (H Morrison, L Paterson, B Knowles and M Rae, Mana Maori and Christianity, Huia Press, 2012).

The Patete report refers to some colourful old stories about Hoera Te Ruruku, not all flattering, and a couple of photos of a very distinguished man can be found easily online. His daughter Wetekia is if anything even more well-known; the book Angelina by Gerard Hindmarsh contains a marvellous account of Wetekia and her friendship with the Moleta family, European settlers at Waitai, across from Puangiangi on D’Urville.

The Patete report later has Messrs Fuller and McCormick leasing Puangiangi, possibly informally, in the 1890s. Several letters from Fuller and McCormick are in the National Archives and their letterhead says they were General Storekeepers in Seddon and most likely Picton. They also farmed Patuki on D’Urville, directly across the channel from Puangiangi.

There is no physical trace, apart from the now-reverting pasture land, of Hoera Te Ruruku or Messrs Fuller and McCormick on Puangiangi. Mr Ruruku’s descendants are very prominent in the area today though, and it’s especially appropriate that we travel to the island most times courtesy of Roma and Lindsay Elkington, great-grandsons of (Roma) Hoera Te Ruruku.

By about ten years after the 1895 partitioning of D’Urville, the Native Land Court Act 1894 was being used to allow land to be sold, if at least a third of the owners agreed, and if all owners retained enough other land to make a living from. So, for example, in 1907 Hugh Gully (Barrister and Solicitor from Wellington, a founding partner of Bell Gully) was leasing Block IX at Port Hardy on D’Urville. In 1908 he had died and his Estate bought out some of the owners and on-sold those shares to Robert John William (Bismark) King-Turner. Mr King-Turner bought out the minorities in 1918-19.

The aforementioned R J W King-Turner, in another letter in the Archives, states that he was leasing Puangiangi from 1920. The letter gives his postal address as Hamilton Bay, near Te Towaka, so it’s reasonable to conclude that Mr King-Turner was farming in several locations, perhaps with a base in Hamilton Bay.

By 1927, sales on D’Urville had been happening for 20 years or more, accelerated by the Native Land Act 1909, which allowed meetings of owners to be called to vote on selling any property where there were more than 10 owners. Such meetings had a quorum of only five owners, regardless of the total number of owners or the proportion of the shares owned by those present. The Native Land Court came to be known disparagingly as Te Kooti Tango Whenua, The Land-taking Court.

The small islands were among the last on the block because they were effectively a single, widely-scattered, parcel owned by all of the original 79 and their successors. In March 1927 though, the islands were partitioned by The Native Land Court on application by Mokau Kawharu. The owners seemed to want partition so that they might also get on and sell, doubtless encouraged by the various lessees including R J W King-Turner.

The owners agreed among themselves who would get which island. The Ruruku whanau became substantial shareholders in Tinui.

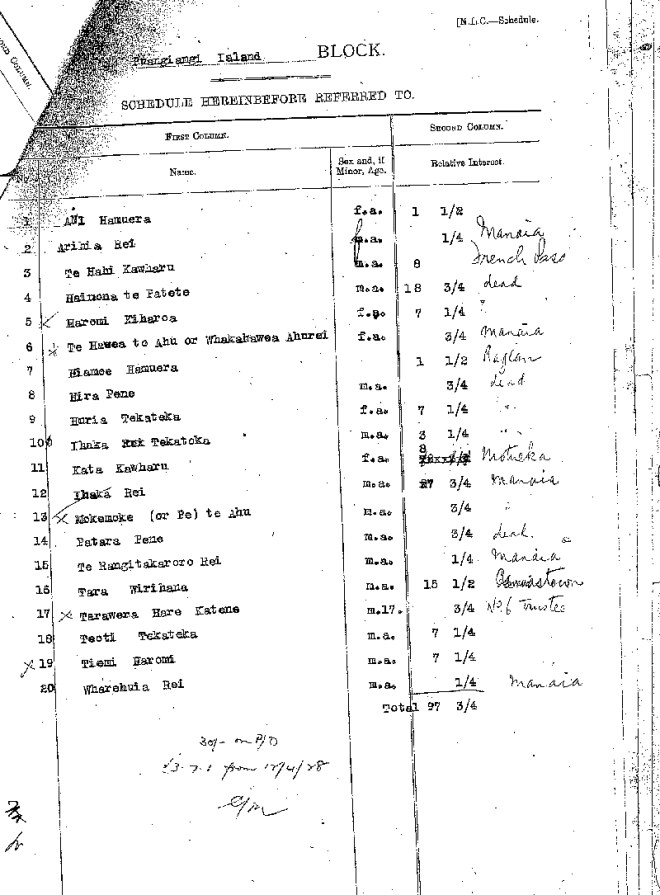

The owners of Puangiangi became, in varying proportions: Ani Hamuera, Arihia Rei, Te Hahi Kawharu, Haimona Te Patete, Haromi Kiharoa, Te Hawea Te Ahu, Hiamoe Hamuera, Hira Pene, Huria Tekateka, Ihaka Tekateka, Kata Kawharu, Ihaka Rei, Mokemoke Te Ahu, Patara Pene, Te Rangitakaroro Rei, Tara Wirihana, Tarawere Hare Katene, Teoti Tekateka, Tiemi Haromi and Wharehuia Rei. At least 6 of the owners were dead by the date of Partition and only a few lived locally- Te Hahi Kawharu at French Pass, Teoti Tekateka and Tiemi Haromi outside the rohe but nearby at Okoha, and Tara Wirihana in Canvastown. The others were scattered widely, but with many minor shareholders being in Manaia.

In December 1926, before partition was completed, R J W King-Turner (Turner in most documents, but I’m using the name used by family today) applied to the Native Land Court and later the Maori Land Board to call a meeting of owners of Puangiangi to vote on the proposal that Mr King-Turner either buy the island at 5% above the Government Valuation, or formalise its lease at £10 per year. Mokau Kawharu and Te Hahi Kawharu were working with him in March 1927 to get the meeting called.

In May 1927, a somewhat perplexed Mr King-Turner wrote to the Registrar of The Native Land Court. He had signed an informal lease with two owners, but became aware that Percy Douglas Hope of French Pass had just signed a one-year lease with three owners, which also gave Hope the right to a 21-year lease or to purchase. Both men were running small flocks on Puangiangi and King-Turner wanted to know if he had the right to impound Hope’s sheep. Further, he was concerned that his investment of £20 to date and the prospect of a valuation fee of £7 to come might be wasted if Mr Hope got in first.

C V Fordham, the Registrar, wrote back within a week of the date of Mr King-Turner’s letter. This is a recurring theme in the records- not only are replies from Government Departments timely, but the postal service is quick. Times have changed. But I digress. Fordham pointed out that neither of the leases was valid because they were not executed by the Board, which would also require a valuation in support of the lease amount. He cautioned against King-Turner impounding Hope’s sheep, or vice-versa. Later, King-Turner was asking if he could at least muster his own sheep into the yards that he had built. Although sheep yards evolve over time, I can therefore be confident in saying that the yards now on Puangiangi date back to the 1920s.

R J W King-Turner supplied the new Government Valuation, of £100, to Fordham in August. Fordham advised that the meeting of owners would require two to be present in person and three others to have provided their proxies. Mokau Kawharu was busy gathering proxies in September. Tara Wirihana (Shadrack Wilson) signed the proxy form in favour of the resolution. He signed with an “X” before a Justice of the Peace. Fordham was unimpressed as Mokau Kawharu was not formally listed as an owner. King-Turner advised that owner Te Hahi Kawharu could attend in person and that he would be able to obtain corrected proxies from Tara Wirihana, Kata Kawharu and Haimona Te Patete. He mentioned that Teoti Tekateka and Tiemi Haromi from Okoha (or Anakoha in other documents; the two localities are a kilometre apart on the shore of Anakoha Bay) were on the other side, having signed the competing lease with P D Hope.

Mr Hope was not idle either, and placed a notice in Kahiti, the te reo version of the Gazette, calling a meeting to consider a sale to him at £125. Tiemi Haromi was holding proxies in favour of selling to Hope, for several owners, including Kata Kawharu and Tara Wirihana whom King-Turner had thought might support his resolution.

The owners were therefore fortunate enough to have at least two competing buyers. In May 1928, Mr King-Turner increased his offer to £140, and the competing resolutions were put to a meeting in Picton on 6 September 1928. Present were owners Tara Wirihana, Teoti Tekateka and Tiemi Haromi, and Te Hahi Kawharu, Tame Patete and Kata Kawharu had given their proxies. Someone made a note in the Alienation File, adding up the interests of the owners present and represented by proxy, and they accounted for the great majority of shares in the island.

Neither Hope nor King-Turner was successful. John Arthur Elkington (Tete Ratapu) came forward as a buyer also. King-Turner upped his offer to £175, but was beaten by Mr Elkington, who was given two months to come up with the purchase price of £195. Mr King-Turner insisted that his cheque for £175 be held by the Board in the event that Mr Elkington was unable to complete, and indeed Judge Gilfedder, President of the Court, was given a mandate to decide what would happen in that event.

John Arthur Elkington was a grandson of Hoera Te Ruruku and he lived nearby at Whareatea on D’Urville. The owners were resolved to accept the highest offer, but might well have been pleased that Puangiangi was to go to a prominent son of Ngati Koata.

The Board was prepared to lend the money to Mr Elkington, secured by First Mortgage over his wife Te Urutahi Manuirirangi’s land at Manaia, accompanied by an assignment of rents. The Registrar advised Mr Elkington by telegraph on 10 October, however, that the loan had been refused. This was apparently because the leases whose rents would be assigned were not formalised. Te Urutahi Manuirirangi wrote back with more detail on the leases and valuation of the land, and Fordham had a change of heart, writing to Gilfedder: “…with due regard to the character of J A Elkington, the applicant’s husband, the security is good for a loan of £300”. Fordham checked with C V Bennett in Manaia (Solicitor, Private Telephone No. 1, Office No. 3- my Dad’s number at the BNZ in Hunterville in the 1960s was 12, which I thought was pretty cool, but 1 and 3 top that) that the rents were being paid on time, as he was collecting them on the Elkingtons’ behalf. Bennett wrote that the lessee was “a good pay” and that there should be no problems.

Fordham also wrote to the Native Land Court in Wanganui to check whether buildings on the property were on Te Urutahi Manuirirangi’s land and so might be used as security. It appeared that she and her siblings had inherited the property and it had only recently been partitioned into individual titles. The valuation at hand covered the undivided property though. The partition order was found, and in it the siblings had agreed that her brother would get the buildings. Another sibling, Akapikirangi, had been bought out by Te Urutahi, subject to a mortgage on Akapikirangi’s portion, securing a loan of £345.

Right on expiry of the two-month period though, Bennett wrote that the loan of £345 was secured over the entire block of land, and that to boot Bennett was Second Mortgagee to the tune of £80. The loan to buy Puangiangi was promptly denied. Mr Elkington visited both the Registrar in Wellington and Bennett in Manaia and was insistent that the loan was secured over only part of the land. Bennett then urgently wired, and wrote, to Fordham to say that the mortgage was indeed only over one parcel. Registrar Fordham wrote to the President of the Court, Judge Gilfedder: “Seeing Elkington’s evident earnestness in this matter and the efforts he is making to complete, perhaps you may consider extending the time for another month from this date, as it appears that Bennett was mistaken and it would be hardly fair to penalise Elkington.”

Things seemed to be back on track and Fordham was writing to Mr Elkington on 19 November to sort out assignment of the rents for the land up in Manaia. The same day he wrote to J J McGrath, Solicitor, in Wellington, asking him to draw up documents for a loan of £250 for 5 years at 8%, reducible to 6.5% for prompt payment.

J J McGrath advised he would need to search the title of the Manaia land in the office in New Plymouth.

Meanwhile, some of the owners were pressing for completion, and word was getting out of the difficulties in raising finance. Douglas Hope’s agent wrote to Judge Gilfedder, offering £182. Teoti Ihaka Tekateka wrote on 16 November 1928 to Gilfedder also, reminding him of the expiry of the two months and his desire to sell to Bismark Turner if Arthur Elkington could not complete immediately.

Interestingly the letter from Mr Tekateka, a reasonably local resident in Anakoha Bay, Pelorus Sound, refers to Puangiangi also as Rabbit Island. Rabbit Island is today an alternative name for Anatakupu, close in to French Pass. An owner who had long moved away- or even whose parents had long moved away- from the district, might use that name in error, but it’s interesting to see it used by a local. Rabbit Island is not an uncommon epithet, though, and it also appears in the next instalment of this story. It’s not unheard of for modern names to be in need of correction, but maybe all we can take from this is simply that Puangiangi at one time held rabbits.

J J McGrath duly completed the title search, and it appeared that the loan was indeed secured over the whole block of Manaia land, but it was something that, given time, could be sorted out by re-allocating the mortgage to only the portion purchased from Akapikirangi Manuirirangi. By then, the extra month was all but up, and Fordham wrote to Mr Elkington on 11 December 1928, denying the loan for a final time.

At this distance it’s hard to conclude whether what happened ought to have happened. From the Board’s viewpoint, they had received instruction to turn down two cash offers in favour of one with a two-month finance clause, had given an extension, and they were under pressure from the owners to call time and sell to the under-bidder, who had offered a good percentage over the Government Valuation anyway. It’s tempting to point the finger at Mr Bennett, the country solicitor, but maybe an error was made in New Plymouth drawing up the titles, despite an accurate instruction. The Elkingtons seem to have been on-to-it concerning the legal complexities, but maybe they would have been overstretching themselves anyway given that the Great Depression was around the corner.

By January 1929 Teoti Tekateka was getting insistent, writing to Fordham: “We have waited long enough for that money, and cannot wait any longer”. On 17 January, R J W King-Turner wrote to Judge Gilfedder, increasing his offer to £185. The offer was accepted by wire on the 19th, and Board minutes show the transfer being executed on 19 February 1929.

Part 2 will follow the King-Turner family on Puangiangi.

Postscript: those closely involved with the project will know that the names Hoera and Kapakapapanui have gained modern-day significance on the island, by kind permission and suggestion of whanau. The wrongs perpetrated against Ngati Koata were settled finally in its 2012 Treaty settlement with the government. John Arthur Elkington went on to serve with the 28th Battalion, and was killed in the Western Desert in November 1942. His name is on a memorial on the Picton-Nelson road, along with that of L B H Hope, son of Percy Douglas Hope.

Main Sources:

Te Tau Ihu O Te Waka A Maui, Wai 785, Waitangi Tribunal 2008 (downloadable from the Ministry of Justice’s website).

Anthony Patete, D’Urville Island (Rangitoto ki Te Tonga) in the Northern South Island, October 1997 report to Waitangi Tribunal concerning Wai 102 (downloadable from Ngati Koata Trust’s website).

Archives New Zealand File AEGV 19119 MLCW2218/7, Record 102, Alienations (South Island)- Puangiangi Island (can be viewed freely in the reading room in Wellington).

This option would allow seabirds to establish, and the forest would over time regenerate to what it would have been, minus any lost taxa. The populations of the existing animals plus any that could get themselves there would increase as habitat improved. The outcome would be a fully functional seabird island typical of Cook Strait.

This option would allow seabirds to establish, and the forest would over time regenerate to what it would have been, minus any lost taxa. The populations of the existing animals plus any that could get themselves there would increase as habitat improved. The outcome would be a fully functional seabird island typical of Cook Strait. The reintroduction of species not on the island but which should be, gives an ecosystem rather close to what it would have been before humans and pests came along. If threatened species were included in translocations, it would help their security by giving them an additional site.

The reintroduction of species not on the island but which should be, gives an ecosystem rather close to what it would have been before humans and pests came along. If threatened species were included in translocations, it would help their security by giving them an additional site. The island could be made available to house acutely threatened species, possibly at some detriment to an ecological restoration intended to provide a typical assemblage of plants and animals.

The island could be made available to house acutely threatened species, possibly at some detriment to an ecological restoration intended to provide a typical assemblage of plants and animals.